The Making of Macintosh (Part 1)

Based on “Apple Confidential 2.0” by Owen W. Linzmayer

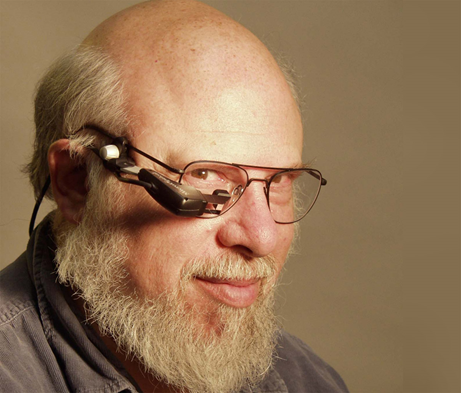

http://biografieonline.it/biografia-jef-raskin

Steve Jobs and the Macintosh are inextricably linked in the minds of most people. So it may come as somewhat of a surprise to learn that the Mac was not his idea at all. In fact, he actually wanted to kill the project in its infancy. Luckily for Apple and millions of dedicated Mac users everywhere, he wasn’t successful.

The true father of the Macintosh was Jeffrey Frank “Jef” Raskin, a professor turned computer consultant. In the spring of 1979, Jobs was still working on the Lisa, a more business oriented PC, but the company was looking for a lower- cost product than the Apple II which was selling for more than $1000.

« […], there was this thing that I’d be dreaming of for some time which I called Macintosh. The biggest thing about it was that it would be designed from a human factors perspective, which at that time was totally incomprehensible. » Jef Raskin.

Raskin had grown increasingly frustrated at the complexity of the Apple II. It was so flexible that users had to be some pseudo-technicians and it was extremely complex for developers to create products that worked with all its configurations.

“Considerations such as these led me to conceive the basic architecture and guiding principles of the Macintosh project,” explains Raskin. “There were to be no peripheral slots so that the customers never had to see the inside of the Machine (although external ports would be provided): there was a fixed memory size so that all applications would run on all Macintoshes; the screen, keyboard, and mass storage device (and, we hoped, a printer) were to be built in so that the customer got a truly complete system, and so that we could control the appearance of characters and graphics.”

Portability was a key concern for Raskin, as he expected his customers to grow so fond of their Macs that they would never want to leave home without. It should also weigh less than 20 pounds and be provided with a 2-hour internal battery. His wish list also included an 8-bit microprocesor with 64k of RAM, one serial port, a modern, real time clock, printer, 4 or 5-inch diagonal screen and a 200k, 5.25-inch floppy disc drive all built in.

Raskin described a user interface in which everything – writing, calculating, drafting, painting etc.- was accomplished in a graphical word processor-type environment with a few and easily learned concepts. “The traditional concept of an operating system islaced by an extension of the idea of an on-line editor”.

He even proposed an official name for his Macintosh computer: the Apple V, a computer that could enter production before Christmas 1981 with an initial end-user price of $500.

As he brainstormed, he kept coming up with more wonderful things to add to his computer. It didn’t take him long to realize that he couldn’t everything he wanted and still produce a $500 price tag computer.

Raskin needed someone to turn his ideas into prototypes. He made Burrel Carver Smith the second member of the Mac team and later on Steve Wozniak began part-time work on the Mac, but Smith continued doing most of the detailed electronic design and breadboarding.

The Macintosh research project was not destined to become an actual product any time soon and Raskin himself did everything he could to “keep the project from burgeoning into a huge, expensive, and time-consuming effort.”